In 1977 J.J. Gibson wrote of "the Theory of Affordances." Essentially what this means as it relates to landscape design is that humans see “affordances” in the landscape – what a scene or object offers. We react to a scene based upon what these objects or scenes offer as far as the individual is concerned. Perception is viewed as not merely dealing with information about the environment, but it’s possibilities as far as human interaction and purposes are concerned.

Later on, Rachel Kaplan and Stephen Kaplan (Professors at University of Michigan) theorized on people interaction with their environments. “Humans react to the visual environment in essential two interrelated ways: the two dimensional pattern, as if the environment in front of them were a flat picture and the three dimensional pattern of space that unfolds before them.

They like the visual array to a photograph, the pattern of information with it, the shades of grey, simplicity of scene/detail and how it “makes sense” to the viewer. The pattern of information on the surface of a photograph can be easier or harder to organize.

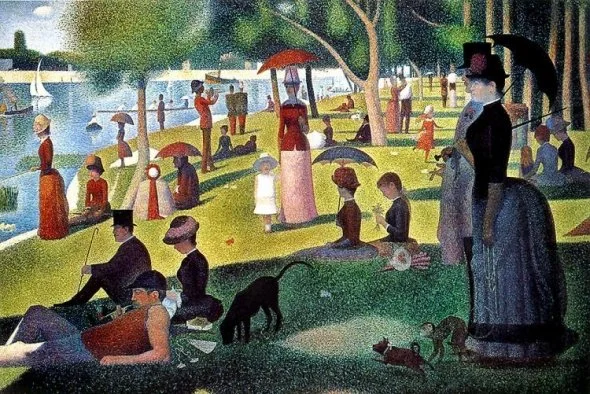

Complexity reflects how much is going on in a scene, how much is there to look at, how rich and diverse the aesthetics/elements are.

George Seurat, Afternoon on the Isle of La Grande Jatte 1884

Coherence reflects the simplicity, organizational components of a scene, that which makes it easier to comprehend, it should all “fit together.” In other words, “something that draws one’s attention within the scene should turn out to be an important object, a boundary between regions or some other significant property.

Hieronymus Bosch, Garden of Earthly Delights 1503-4

Research evidence also begins to suggest that the capacity of working memory for most people to hold approximately is five chunks/groupings of information in their working memory at any one time. Kaplan therefore propose that dividing a scene into five major areas or groupings makes it easier or more appealing, comfortable in terms of coherence for the viewer of the scene.

Because landscapes are essentially three dimensional when viewed, but four dimensional with the addition of “time”, people interpret a landscape whether viewed or experienced as three-dimensional. In

Jay Appleton’s “Prospect-Refuge theory" there are “implications both in terms of informational opportunities and informational dangers.” Gathering these opportunities, having some comfort level with them is what leads to another component called Mystery. Mystery in this context is all about surprise and the promise/attraction assumed within the scene of new information. What encourages us to discover more. A scene that is partially obscured by foliage, a path that is tempting to follow but you’re not sure where it leads. “A scene high in mystery is one in which one could learn more if one were to proceed further into the scene.” “Mystery evokes curiosity. What it evokes is not a blank state of mind but what might be coming next.”

W. Eugene Smith, The Walk to Paradise 1946

Appleton stresses safety in Prospect-Refuge theory. Kaplan takes it one step further in his last component to one that “makes sense” or is legible. “Legibility” entails a promise or a prediction.

” It allows the viewer to assume a way to navigate through the space and out of it, an organization of the ground plane. With a sense of depth and well-defined space, smooth textures and elements well distributed, the viewer is comfortable moving within the space.

Concepts to ponder when designing space.

Preference Matrix by Kaplan above.

1. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective: Rachel & Stephen Kaplan, University of Cambridge 1989

2. Ibid

3. Ibid

4. Ibid